Edward

Shapiro

MACROECONOMIC ANALYSIS

Chapter 17: The Classical Theory

|

Index THE CLASSICAL THEORY The Level of Output and

Employment in Classical Theory Say’s

Law The Quantity Theory of

Money

The Quantity Theory as a Theory of the Price

Level The Quantity Theory as a Theory of Aggregate Demand Classical Model without

Saving and Investment

Effects of a Change in the Supply of Money

Effect of a Change in the Supply of Labor

Effects of a Change in the Demand for Labor

Effects of a Rigid Money Wage Monetary Policy and Full Employment Web 4

Classical Model with Saving

and Investment |

CLASSICAL MODEL WITH SAVING

AND INVESTMENT

Although formally correct,

the classical model we have been discussing is oversimplified because it fails

to break aggregate demand down into demand for consumption goods and demand for

capital goods. This means that it

does not recognize the processes of saving and

investment.

We must now recognize that

not every dollar of income earned in the course of production is spent for

consumption goods; some part of this income is withheld from consumption, or

saved. Clearly, unless there is a

dollar of planned investment spending for every dollar of income saved, Say’s

Law is invalidated. Another part of

classical theory provides the mechanism that presumably assures that planned

saving will not exceed planned investment.

This mechanism is the rate

of interest. Classical theory

treated saving as a direct function of the rate of interest and investment as an

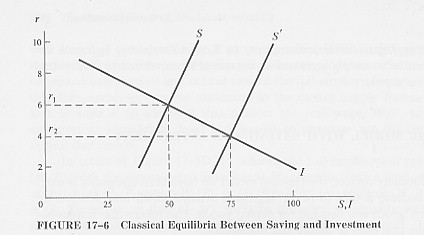

inverse function, as illustrated in Figure 17-6. The investment curve is simply the curve

of the marginal efficiency of investment (MET), whose derivation was explained

in some detail in Chapter 11. There

it was a part of our development of Keynesian theory; here we see that this was

actually a part of the classical theory taken over by Keynes. It is important to note, however, that

although both theories show investment as an inverse function of the rate of

interest, this is not to say that both assign equal importance to the rate of

interest as an influence on investment spending. The whole question of the elasticity of

the investment demand schedule is involved, a topic we discussed at length in

Chapter 13. Keynes and most

economists since Keynes have argued that the curve is relatively inelastic.

If it is elastic, a relatively

small change in the rate of interest will be sufficient to call forth a

relatively large change in investment; relatively small changes in the rate of

interest will then be all that are required to keep planned saving and planned

investment in balance as the saving and investment schedules shift. If it is inelastic, relatively large

changes in the rate of interest will be required for this purpose. 14

The question then arises

as to whether the

14. It is also conceivable

that both the investment and saving curves are so inelastic that a shift to the

right in the saving curve or a shift to the left in the investment curve or a

combination of the two may result in an intersection of the two curves only at a

negative rate of interest. However

low the rate of interest might fall, it assuredly could not fall below zero.

The result is an impasse at which

the rate of interest is completely powerless to equate saving and

investment. See W.S. Vickrey,

op. cit., pp. 172-73.

357

rate of interest will

fluctuate freely over the wider range necessary to equate saving and investment.

To simplify the exposition of the

classical system, let us assume here that the curve is indeed elastic, so that

investment is relatively responsive to changes in the rate of interest. Small changes will then keep saving and

investment in balance.

The saving curve of Figure

17-6 is new. Here saving is made a

direct function of the interest rate; in Keynesian theory, saving is a direct

function of the level of income. The rate of interest may have an

influence on saving, but it is of minor importance in the Keynesian scheme.

In classical theory, the rate of

interest is all important, and the level of income is of minor importance. Since the classical model argues that

full employment is the normal state of affairs in the economy, the level of

income is in effect ruled out as a variable in the short run, and so it is ruled

out as an influence on the amount of saving. The problem in classical economics is to

explain how saving will vary at the full-employment level of income, and the

solution is provided by the rate of interest. The higher the rate of interest, the

greater the amount of the full-employment income that is withheld from

consumption or devoted to saving.

Given saving and investment

curves such as S and I of Figure 17-6,

competition between savers and investors would move the rate of interest to the

level that equated saving and investment. If the rate were above r1, there would be more funds

supplied by savers than demanded by investors, and the competition among savers

to find investors would force the rate down. If the rate were below r1,

competition would force the rate up. When the rate is at r1, equilibrium

is established, with every dollar saved or withheld from consumption spending

matched by a dollar borrowed and devoted to investment

spending.

It is important to see that

this transfer of money from savers to investors also involves a transfer of

resources. The decision to save

part of current income is a decision by income recipients not to exercise their

claims to the full amount of output that results from their productive services.

This releases resources from the

production of consumption goods and makes them available for the production of

capital goods. These resources will

be fully absorbed in the production of capital goods only if investors choose to

purchase exactly the amount

358

of capital goods that can

be produced by the resources released as a result of saving. This means that if the rate of interest

were above r1 and somehow stayed above r1, unemployed

resources would appear, for the excess of S over I at an interest rate above

r1 reflects, in real terms, an excess of resources released

from the production of consumption goods over the amount absorbed in the

production of capital goods. One of

these resources is, of course, labor, and the excess of S over I also means that there is

an excess of labor available over labor employed. In a word, there is unemployment. Thus, in the classical system, if the

rate of interest fails to equate saving and investment, it also fails in its

assigned task of promptly reallocating the resources released from production of

consumption goods to the production of capital goods, and unemployed resources

are the result.

Changes in Saving and

Investment

As long as the interest

rate adjusts upward and downward to correct any disequilibrium, shifts in the

saving and investment functions will lead to the establishment of new

equilibrium positions. Suppose that

income recipients become more thrifty; at each rate of interest they choose to

save a larger part of their current income. This appears in Figure 17-6 as a shift to

the right from S to S’ in the saving curve and a decrease in

the rate of interest from r1 to the new equilibrium level

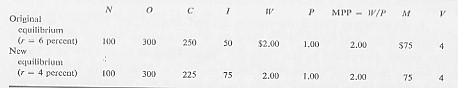

r2. A numerical

example such as those presented earlier is given below to bring out the effects

of an increase in thrift in the classical system. The first row indicates the values of the

variables at the original full-employment equilibrium. Full employment of the labor force is

N of 100, and full-employment output is O of 300. With the interest rate at

r1, say 6 percent, the real income of 300 was divided into 250

of consumption and 50 of saving; r of 6 percent also produced

equilibrium with saving of 50 and investment of 50. If the saving curve

now shifts to the right and the interest rate drops to r2, say 4

percent, a new equilibrium is established at which saving of 75 (in real terms,

O of 300 less C of 225) equals investment

of 75. With no shift in the

production function or the supply of labor, full-employment output remains at

300. The only change is in the

distribution of output from 250 of consumption goods and 50 of capital goods to

225 of consumption goods and 75 of capital goods. Thus we see that the increased

thriftiness of the public has produced a reallocation of resources - one away

from the production of consumption goods and to the production of capital goods

- but with the total production of goods unchanged at the full-employment level

of 300.

359

If the saving function

shifted in the opposite direction so that there was less saving at each rate of

interest, we would have a higher rate of interest at which a smaller flow of

saving would be equated with a smaller flow of investment but still with the

flow of aggregate output unchanged from the full-employment level with which we

started. The effects of shifts in

the investment curve resulting from shifts in the MEC curve may be traced in the

same way. Whatever the shifts in

the saving and investment curves, however, the possibility of “oversaving” or

“underconsumption” could not arise as long as the interest rate succeeded in

balancing saving and investment.

Does the interest rate

always promptly adjust as required to maintain equality between saving and

investment? The Swedish economist

Knut Wicksell (1851-1926)

was one of the first to point out that there are conditions under

which it would not. However, the

full-employment conclusion would still result if prices and wages were

sufficiently flexible. If the

interest rate did not promptly adjust, there would be an excess of planned

saving over planned investment or planned investment over planned saving. According to Keynesian theory, a fall or

rise in income (output and employment) would be required at this point to bring

saving and investment back into balance. This was not the case in classical

theory, however. An excess of

saving over investment would mean a deficiency of aggregate demand at the

existing price level. This would

lead to a deflation of prices and wages but would not interfere with the

maintenance of the real wage consistent with full employment. Aggregate demand that had become

deficient at the original price level would now be adequate to purchase the

full-employment level of output at a lower price level. Conversely, an excess of planned

investment over planned saving would mean an excess of aggregate demand at the

existing price level. This would

lead to an inflation of prices and wages but again would not interfere with the

maintenance of the real wage consistent with full

employment.

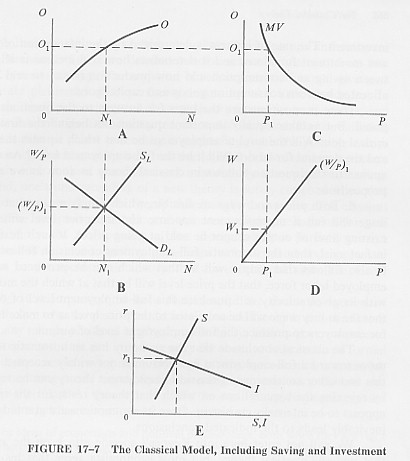

The purpose of this chapter

has been to show, in terms of a simple model, how classical theory answered the

fundamental questions of macroeconomics. What determines the levels of employment,

output, consumption, saving, investment, prices, and wages? Our discussion may now be summarized in a

list of the basic propositions that make up classical theory. Each of these propositions will be

related to the graphic apparatus of Figure 17-7, which adds nothing new but

brings together the saving-investment branch of the classical system with its

other branches, presented in two steps in the preceding pages.

-

1. As shown in Part B, the supply, SL, and demand, DL, for labor are both

functions of the real wage, W/P.

Because of diminishing

returns, the demand curve slopes downward to the right (i.e., more labor is

hired only at a lower real wage). Because of the essential

disagreeableness of work, the supply curve slopes upward to the right (i.e.,

more labor is offered only at a higher real wage).

360

The intersection of the

supply and demand curves thus determines both the real wage (W/P)1 and the level of

employment N1.

2. With fixed techniques of

production and fixed capital stock, output in the short run becomes a function

of employment, as shown by the production function in Part A. With employment determined in Part B as

N1, output is determined

in Part A as O1.

3. The price level, P, is determined by the supply of money,

M, the curve MV in Part C defining the particular

supply of money and a stable velocity of money. With output determined in Part A as O1, the price level of that

output is determined on Part C as P1.

4. The money wage, W, adjusts to the price level to produce

the real wage required for equilibrium.

With the equilibrium real wage determined in Part B as (W/P)1 and the price level

determined in Part C as P1, the required money wage

is determined in Part D as W1.

5. As shown in Part E,

saving, S, is a direct function of

the rate of interest; and investment, I, is an inverse function of the

rate of interest. With the rate of

interest as a measure of the reward for saving, the higher the rate of interest

the greater will be the volume of saving.

With the interest rate as the “price” of capital goods, the lower the

interest rate, the greater will be the volume of

361

investment. The rate of interest is determined by the

intersection of the saving and investment functions, and it determines how real

income is allocated between saving and consumption and how production (equal to

real income) is allocated between consumption goods and capital

goods.

These propositions are the

basis for answers to the questions originally posed. But another equally important question

lies behind the first and most critical one: Will the level of employment be

that which equates the supply of and the demand for labor? Will it be the full-employment level?

An affirmative answer to this

question follows in classical theory as soon as we add a final

proposition:

6. Both prices and wage are

flexible, which simply means that the money wage will fall if unemployment

appears, and the price level will fall if the existing level of output cannot be

sold at going prices. If such

flexibility does in fact exist, then the automatic full-employment conclusion

follows logically. It also follows

that output will be that which can be produced with a fully employed labor

force, that the price level will be that at which the money supply with its

given velocity will purchase this full-employment level of output, and that the

money wage will be so related to the price level as to make it profitable for

employers to produce the full-employment level of

output.

The classical conclusion

that the economy has an automatic tendency to move toward a full-employment

equilibrium is not widely accepted today. But this and other conclusions of

classical employment theory can be rejected only by rejecting the assumptions on

which that theory rests, for the theory itself appears to be internally

consistent. Once its assumptions

are granted, the theory inevitably leads to the indicated

conclusions.

We will not enter here into

Keynes’s specific attack on the assumptions that underlie classical theory, but

most economists agree that his attack was successful. Not only did he offer persuasive

arguments against these critical assumptions, but he replaced the rejected

assumptions with others that appeared much more consistent with the facts of

ordinary observation and statistical evidence. To the extent that the assumptions on

which the classical theory was based could be shown to be unacceptable, the

conclusions, including the automatic full-employment conclusion, reached by that

theory also became unacceptable.

A CONCLUDING

NOTE

If the classical analysis

of the process by which the levels of employment, output, and prices are

determined is unacceptable, at least in its application to the modern economy,

it may appear that this lengthy chapter is basically unnecessary. To this there are a number of

replies.

First, it is not altogether

correct to label the classical theory of employment. output. and prices as

unacceptable or in some sense

“wrong”. Since the aim of this chapter was to do

no more than introduce the broad outlines

of

362

that theory, it could do no

more than draw broad conclusions and compare these with the somewhat more

detailed conclusions so far derived from our study of Keynesian theory. The omission of refinements that would

give us a more accurate picture of classical theory leaves us with little choice

but to categorize the basic propositions of classical theory as correct or

incorrect, and such categorization is itself inherently incorrect. Alfred Marshall once said that every

short statement about economics is misleading (with the possible

exception of this one). Our

statement here, relative to what is involved in a complete treatment, is such a

short statement and unavoidably somewhat

misleading.

Second, one’s understanding

of a new theory is surely enriched when that theory is contrasted with the old

theory that it seeks to displace. The classical system was the accepted

explanation of macroeconomic phenomena for well over a hundred years. A discussion of this theory, which is

partially correct and a product of the not so distant past, helps us understand

and appreciate the changes in macroeconomic theory that have occurred since the

Great Depression.

Finally, it is important to

note that, despite the dramatic success of Keynesian theory over the past three

decades, classical theory is still the theory on which many men in positions of

great responsibility, both in government and business, were raised. It is not even necessary for them to have

received formal training in economics as young men - the stuff of which

economics is made has a way of permeating men’s minds and influencing their

outlooks without any awareness on their part. At the very end of the General Theory,

Keynes expressed this thought in what has come to be a much-quoted

statement:

the ideas of economists and

political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are

more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else.

Practical men, who believe

themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the

slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in

the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years

back. 15

The defunct economists who

continue to influence many of these men today are the economists who constructed

the classical theory.

In a similar vein, we find

the very last sentence in Alexander Gray’s classic little handbook on economic

thought:

No point of view, once

expressed, ever seems wholly to die; and in periods

of transition like the

present, our ears are full of the whisperings of dead

men.16

For more than one reason,

the teachings of the classical economists are of something more than historical

interest today. The few reasons

here given should be sufficient to make this point. The “Keynesian Revolution” did not so

completely wipe out the “old order” that no sign of it remains today. So far at least, for both academic and

practical reasons, a proper introduction to macroeconomic theory should include

the fundamentals of the theory that held sway for more than a century before

Keynes.

15. General Theory, p.

383.

16. The Development of Economic Doctrine,

Longman, Green, 1931, p. 370.

363

End of Chapter